Sammy Solo's Salute to the Maliseet TrailWelcome Page |

Sammy Solo's Lament for the Lost Maliseet Trail:

As Published in No Umbrella, and The Woodstock Bugle Observer

Sammy Says: "This Lament was written in the winter of 2004-05, before the Crossing of 2005, and was not published until after the crossing. This edition was reworked to include information published in W.E. (Gary) Campbell's 2005 book "Road To Canada". Hope you enjoy...."

The Maliseet Trail: The Pre-Contact Period.

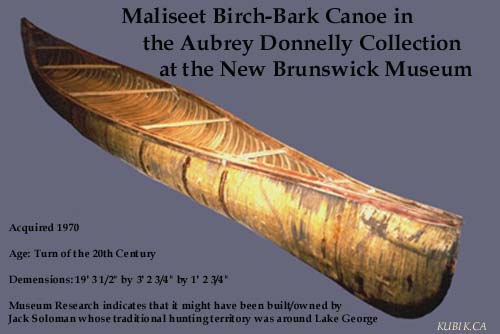

The Maliseet Trail was one of the most important routes traveled by the semi-nomadic peoples we now call the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot First Nations(1). Reports of portage trails with solid rock furrowed by the moccasins of the native tribes led to speculation in the 1800s that the Trail was the earliest evidence of man in Eastern North America(2). Its central inland location, and intersections with three major river drainages, made the Pre-Contact Trail a well-known and long used corridor of travel. Describing the Trail as an ancient route comprised of 200 kilometers of paddling and 20 kilometers of portaging does not do it justice. The Trail was an arterial route that connected the Maliseet's ancient Fort Medoctec (12 kms south of today's Woodstock, NB, Can.) to the Penobscot's Indian Island (just north of today's Old Town, ME, USA) by passing through Passamaquoddy territory and linking the drainage systems of the Saint John, Saint Croix, and Penobscot Rivers. The Trail was an important link in the original world wide waterway (www) of pre-contact Eastern North America.This Trail, like so many other waterways, supported and gave rise to that most efficient craft of superior qualities we call the birch-bark canoe. A craft which arriving Europeans adopted without modification for forest travel (3) and which, in this writers opinion, modern man has yet to equal.

The ancient Pre-Contract Trail existed in a place and time when highly skilled peoples perfected their canoes using environmentally-appropriate materials and technologies. It should be no surprise then the eastern terminus of the Trail was where a 19-year-old Edwin Tappan Adney would begin his interest in the birch-bark canoe. Adney's interest grew into a life study which many accredit as being an import factor in the survival of the birch-bark canoe(4) .

(1) WF Ganong: A monograph of historic sites in the province of New Brunswick. Ottawa: J. Hope, 1899 Reprint: Historic Sites in the Province of NB, St. Stephen, N.B.: Print'n Press, 1983

(2) Gesner

(3) ET Adney and HI Chapelle: P(3) The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America: Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1964.

(4) ET Adney and HI Chapelle: P(4) The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America: Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1964.

The Maliseet Trail: The Post-Contact Period.Arriving Europeans found new uses for the Maliseet Trail including settlement, deforestation, and war. In the post-contact era, the Trail was quickly put into service as France and England fought for control of Eastern North America. The Trail became a warpath capable of taking one quickly and directly from the heartland of Acadia to New England. During the period of la petite guerre, 1687 to 1697, the Trail was used to further inter-European hostilities and the desire for control of more territory. Meductic was a place for French-led war parties gathered before advancing west, first over the Benton portage, to forward positions at Castine, Maine(5).

In 1689, a group of New England colonialists were kidnapped from Pemaquid, in modern day Maine, taken north across the Trail, tortured and sold into slavery as retaliation in a French-English war(6). Among the captives was 14 year old John Gyles who would live among the Maliseet for 6 years and in 1736 published his memoirs entitled Memoirs of Odd Adventures, Strange Deliverances, Etc. In the Captivity of John Gyles, Esq., Commander of the Garrison on Saint George River in the District of Maine, Written by Himself. This account of life among in the first nations remains an important historical text.

When the age-old French-English hostilities were replaced by new ones between an American Republic and England, the Maliseet Trail was again pressed into diplomatic and war service.

In February 1776, General Washington sent gifts and letters of friendship to Maliseet and Mi'kmaq leaders. Later that same year, Maliseet leaders Pierre Tomah and Ambroise St. Aubin, traveled to Delaware and met General George Washington to discuss their support for his revolutionary cause. In the fall of 1776, following the failed siege of Fort Cumberland, part of Colonel Jonathan Eddy's "army" fled to Machias, Maine along the Eel River portage route. In 1777, Washington's emissary, Colonel John Allan, attempted another invasion of Nova Scotia. He traveled to Meductic and established a base at Aukpaque, just north of Fredericton, among the Pro-Continental Congress Maliseets. In June, Allan learned that a large number of British troops were moving up the Saint John River to act against them. In July, Col. Allan and a party of 480 Maliseets in 128 canoes crossed the Trail in order to find safety in the New Republic(7) .

According to local folklore, it was during the July, 1777 crossing of the Trail that a Maliseet golden treasure was buried and lost on the Meductic portage(8). As the Maliseets portaged west from Fort Meductic to Benton, a golden idol, "…about the size of a new born critter", was secretly buried by a chief and a young man. The Maliseets knew the Americans were engaged in an expensive war and they wished to avoid the possibility of being taxed on the value of their gold. Just days after burying the idol, the only two men who knew of the secret location drowned crossing Grand Lake. The idol is said to remain buried somewhere on the 7 km portage to Benton.

The Maliseet Trail's ability to act as a side door into an undefended region of New Brunswick would continue to trouble the British for another 27 years. Allan himself would continue to use the Trail until 1778 for communication with pro-continental congress Maliseets, whose support for the American cause of freedom lead to raids on British vessels, property, and livestock. In the post-Revolutionary War period, the British would twice place small garrisons at the eastern end of the Trail, once during the Chesapeake Affair in 1807, and again during the War of 1812 . The British also had a small detachment at Meductic during the 1860s to apprehend deserters(9).

In 1804, the Trail remains the only route of travel in the area and is used by the first American settlers of Houlton, Maine, who traveled west to the Saint John River then east to Houlton on the Muduxnekeag River. They crossed the Trail as far as North Lake, but became hopelessly on the portage to First Eel River Lake. For several days, they faced starvation before stumbling upon a pioneer's cabin next to the Saint John River(10) .

Tales of near death and hardship on the Trail continued, and in the early 1800s a 10-year old Penobscot boy named Joseph Polis almost met his end crossing westward on the Trail. His hunting party became ice-bound in Grand Lake and the young Polis faced starvation, then near drowning in the icy Mattawamkeag River. Polis lived to become a famous figure in early American literature courtesy of writer, poet, and philosopher, Henry David Thoreau.

In 1857, Joseph Paul Jr. (Polis 11) acted as guide for Henry David Thoreau on the writer's third, and last, excursion into the Maine woods. In July of that year, Paul and Thoreau struck a deal that paid Paul a dollar and a half a day, plus fifty cents a week for his canoe. Paul's initial interest in the trip was said to involve moose hunting with a provision in their deal allowing Paul to keep the skins of any moose they shot. Thoreau provided these interesting details plus a short but accurate description of the Maliseet Trail when Maine Woods was posthumously published in 1864.

By the 1847, the first roads had been built through the wilderness and use of the Trail had decreased to the point where travelers were forced to depend on ink hieroglyphics to find the once well worn route. Dr. Abraham Gesner, New Brunswick's first Provincial Geologist, and later the inventor of kerosene, got lost on the North Lake to Eel River Portage, and then almost plummeted over the falls on the lower Eel River. This happened to Gesner despite being in the company of three native guides. Both times, crude hieroglyphics saved the party from harm(12).

In 1887, a vacationing 21- year-old American from Ohio, named Edwin Tappan Adney, came to Woodstock, where he met a skilled Maliseet named Peter Joe. Two years later, Adney and Joe each build a birch-bark canoe and from this experience Adney made notes and sketches. These were published in 1900 and become the earliest detailed description on a birch-bark canoe complete with instructions for building one. Adney continued a life-long study of birch-bark canoes and left a body of work that included the construction of detailed scale models, drawings, instructions, interviews and correspondence with native builders and Hudson Bay Company employees, articles, and a posthumously published book entitled The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America(13) .(5) WE (Gary) Campbell: P(21), The Road to Canada: The Grand Communications Route from Saint John to Quebec, Fredericton, NB. Goose Lane Editions and The NB Military Heritage Project. 2005.

(6) WO Raymond: P The river St. John: it physical features, legends and history from 1604-1784. Sackville NB, Tribune Press, 1943.

(7) WO Raymond: The river St. John: it physical features, legends and history from 1604-1784. Sackville NB, Tribune Press, 1943.

(8) GF Clarke: Six Salmon Rivers and Another. Fredericton NB, Brunswick Press, 19??

(9) WE (Gary) Campbell: P(41,55, 57 ), The Road to Canada: The Grand Communications Route from Saint John to Quebec, Fredericton, NB. Goose Lane Editions and The NB Military Heritage Project. 2005.

(10) JR Ross: Talk to the Carleton County Historical Society, 1960, unpublished.

(11) Craig Macdonald translates Thoreau's word "Polis" from Algonquin to English as Paul Jr. which was consistent with Joseph being the Chief's son.(12) JR Ross: Talk to the Carleton County Historical Society, 1960, unpublished

(13) ET Adney and HI Chapelle: P(3) The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America: Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1964.

The Maliseet Trail: The Last Hundred Years.Over the last century, this ancient Trail drew the attention and interest of William Francis Ganong, Dr George Frederick Clarke, Nicholas N. Smith, Dr. Peter L. Paul, J. Robert Ross, Patrick Polchies and Martin Paul. Over the last 50 years, the exact route on Ganong's 1899 sketched maps were contested and debated but no advancements in mapping the Trail were published. One Trail authority speculated that Native Shamans were using supernatural powers to hide the Trail and prevent a successful passage.

In 1963, a Canadian military training exercise on the Trail went awry . In the exact spot where Geologist Gestner narrowly avoided death in 1847, seven Canadian soldiers went over the falls on the Eel River in a 300 pound rubber assault raft. Two soldiers were injured and five stranded on an island until rescuers arrived (14).

In 1964, after 14 years of scouting and research, a crossing was staged by Nicholas N. Smith and Dr. Peter L. Paul. The men ran into trouble from the start and were eventually stopped only 6 miles from the intended end point of Indian Island, ME. Windy weather and dysentery proved to be the final blows to the crossing(15). But the trouble did not end there. Smith's 35mm camera film was spoiled by moisture on the crossing and his 16mm movie film from the trip was lost by the processor and never returned to Smith(16).

In 1994, the two-man team of Pat Polchies and Martin Paul completed the paddling portions of the Trail, but 10 years later, as 2004 drew to a close, neither was willing to discuss their experience or provide advice to this author. In 1996, a New Brunswick film production company shot a video reenactment of the earlier crossing and filmed expensive air footage of the route. Nine years later, that material remains unreleased.The history of the Maliseet Trail encompasses several thousand years, two hundred km of paddling, twenty km of portaging, nine bodies of water, four First Nations, two European Nations, and two New Nations. The story of the Trail is too rarely told, has been partially lost, largely abandoned, but not completely forgotten.

(14) J. Robert Ross: 1964 Letter to Nicholas Smith, Collection on Nicholas Smith, unpublished.(15) Nicholas N. Smith, The Old Trail: Maine Archaeological Bulletin 1(2):13-14, 1964(16) Nicholas N. Smith: 2005 Letter to author, unpublished.

The Maliseet Trail: Today

Today, the Trail's exact portage routes and precise trailheads are unknown, unmarked, and unmapped. Ironic when you consider Allan Morantz's view that "...early European explorers used their own maps to write Native people off their own land."(17) If surveying and mapping were the very things that led to the end of the Pre-Contact Maliseet way of life, and thus the demise of the Trail, then perhaps Nicholas N. Smith was onto something in 1964 when he speculated that "... Indian Shaman wished to retain the secret of the Old Trail.(18)"

(17)Alan Morantz, Where Is Here?: Canada's Maps and the Stories They Tell. 2002

(18) Nicholas N. Smith, The Old Trail: Maine Archaeological Bulletin 1(2):13-14, 1964.

Post Script -

In Old Town Maine, on May 29th 2005, a rain-beaten, and trail-weary, party of 8 paddlers stepped out of 4 canoes to complete a successful crossing of the Maliseet Trail. The 9-day crossing was in almost constant rain with most of the daily temperature averaging near or below 10 C. Despite the obvious hardships, the crossing was made without accident, incident, or argument.

Members of the Crossing of 2005 were: Mike Grant, Beth Johnston, Dino KubiK, Nancy Macdonald, and Paul Meyer all of Fredericton NB; Matt Hopkinson of Hubbardston MA, USA (aka "Paddle'n Hal" www.vodoocanoe.com); Craig Macdonald of Dwight, ON; and Anthony Reader of St Stephen, NB.

These were not eco-challengers trying to beat the Trail. This was a diverse group, ranging in age from 28 to 68, who were able to combine the skills of the woodlands canoeist with an attitude of respectful appreciation, and a daily practice of leaving tobacco behind at each encampment, to experience the Trail to it's fullest. The Protectorate Shamans did allow the crossing, but retained many of the Trail's best secrets.

Yours in the matters of the Trail,

Sammy Solo. (_;__)

THANKS TO THESE SUPPORTERS OF THE TRAIL...........

Thanks to The Lament's August 2005 Publisher: WWW.NoUmbrella.com

Thanks to the Lament's September, 2005 Publisher: The Woodstock Bugle- Observer